The shifting landscape of chemicals and materials The COVID-19 impact on the chemicals industry

18 minute read

05 October 2020

As in other industries, COVID-19 has impacted the chemicals industry and all its sectors, influencing trends already in play, sometimes in surprising ways. Four scenarios can guide industry players on the way forward.

COVID-19 impacts longer-term trends in chemicals and materials

The first quarter of 2020 was an unanticipated turning point for the oil, gas, and chemicals industries. The dual effects of the COVID-19 ̶ related economic downturn and the oil price collapse reverberated across these industries, which were already grappling with challenging longer-term trends. Three of these trends, in particular, were compounded by the events of early 2020:

- Growing consumer awareness of sustainability has led energy and chemical companies to explore decarbonization technologies, reexamine their assets, and begin to diversify away from hydrocarbons where possible.

- Increased use of digital technologies in the workplace is transforming work and the workforce.

- Chemical companies have been facing a situation of oversupply in certain market segments.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Oil, gas & chemicals collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Consumers are placing higher value on sustainability and thus considering products based on criteria such as circularity and carbon footprint.1 In addition, the consumer concern about carbon emissions has spurred investment in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and decarbonization of transportation. These trends have had an impact on end markets for chemicals, notably in automotive and construction.2 The advent of COVID-19 has further complicated the situation by depressing the automotive and construction sectors (along with many other sectors) and disrupting existing supply chains.

The rise in oil, gas, and chemicals companies’ deployment of digital technologies has been primarily driven by efficiency gains and increased reliability. Advanced market sensing, enhanced optimization of operations, and increased use of “in silico” simulations produced positive results for many companies across these industries.3 With the sudden arrival of COVID-19 and resulting closure of plants and work sites, companies’ existing digital technologies provided an advantage, but, in many cases, were still not adequate for the level of remote working and cybersecurity that was suddenly necessary.

Finally, the dual impact of the pandemic-related shutdown and the March 2020 oil price collapse further exacerbated the oversupply situation that some US chemical producers already faced. The economic downturn depressed demand in local and export markets. Furthermore, the oil price collapse narrowed the feedstock cost advantage US petrochemical companies enjoyed due to their reliance on domestic ethane, making their products potentially less competitive in an even more difficult market.

In the wake of COVID-19, chemical company executives should evaluate how enduring these changes will prove: which are likely to accelerate and offer new opportunity, and which will decelerate and potentially impact their operating environment. We offer four scenarios that, while not predictive, indicate some key signposts to watch in the chemicals sector, and highlight potential areas for opportunity.

The research approach and methodology

As the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic started to emerge in the second quarter of 2020, a research team was assembled to study the impacts of the pandemic and to examine trends, develop scenarios, and propose a future road map for how the chemicals and materials ecosystem could first emerge, and then thrive in the postpandemic economy. This was done through extensive one-on-one interviews with over 30 industry executives from more than 15 global companies. The interviewees’ roles varied from C-suite and general management to functional vice presidents and specialists. The interview results were analyzed qualitatively and semiquantitatively. The identified trends and scenarios were further validated through webinar audience surveys (n=53). This primary research was augmented with comprehensive secondary reviews of business and technical literature and discussions with Deloitte subject matter specialists.

A more detailed examination of the trends and their implications

The chemicals and materials sector is not monolithic but rather a collection of companies that vary in size, geography, business model, and end-market focus. These companies are part of a broad ecosystem, with the raw material inputs of oil, gas, coal, minerals, and bio-based materials on one side and a broad swath of application sectors on the other. Historically, the industry has been segmented as petrochemicals, diversified manufacturers, and specialty chemical companies.

While the broader trends introduced in the previous section apply to the sector as a whole, the complexity of the differences between the different players indicates the importance of examining trends by player segment. In previous research in its multiverse series, Deloitte segmented chemical industry players into three categories: natural owners, differentiated commodities, and solution providers.4 Each of these categories typically has a different strategic imperative. Natural owners—large and vertically integrated—have tended to focus more on continuous improvement and operational excellence than innovation. Differentiated commodities focus on supply chain efficiency, innovation across markets (often called industrial marketing), and cost optimization to thrive in a highly complex and fragmented category. Solution providers do just that: focus on realizing the power of their unique products coupled with application know-how and services.

With this inherent complexity, one would not expect all companies to feel the same effects of a global pandemic and the resulting shifts in consumer and company behaviors. Indeed, the research confirmed that the breadth of impact reflects the diversity of business models in chemicals and materials. That said, the trends can still be broadly categorized across all segments based on the “differences in the rate of change”:

- Certain key trends are accelerating due to the crisis, reshaping both supply and demand across chemicals and materials.

- Other trends have slowed significantly and likely will continue to decelerate or perhaps even reverse.

- Finally, trends that were important before the pandemic will likely continue to shape the industry for the foreseeable future.

Considering trends through this “second derivative” lens can give further insight into the longer-term impact of the pandemic and the emergence of a new status quo.

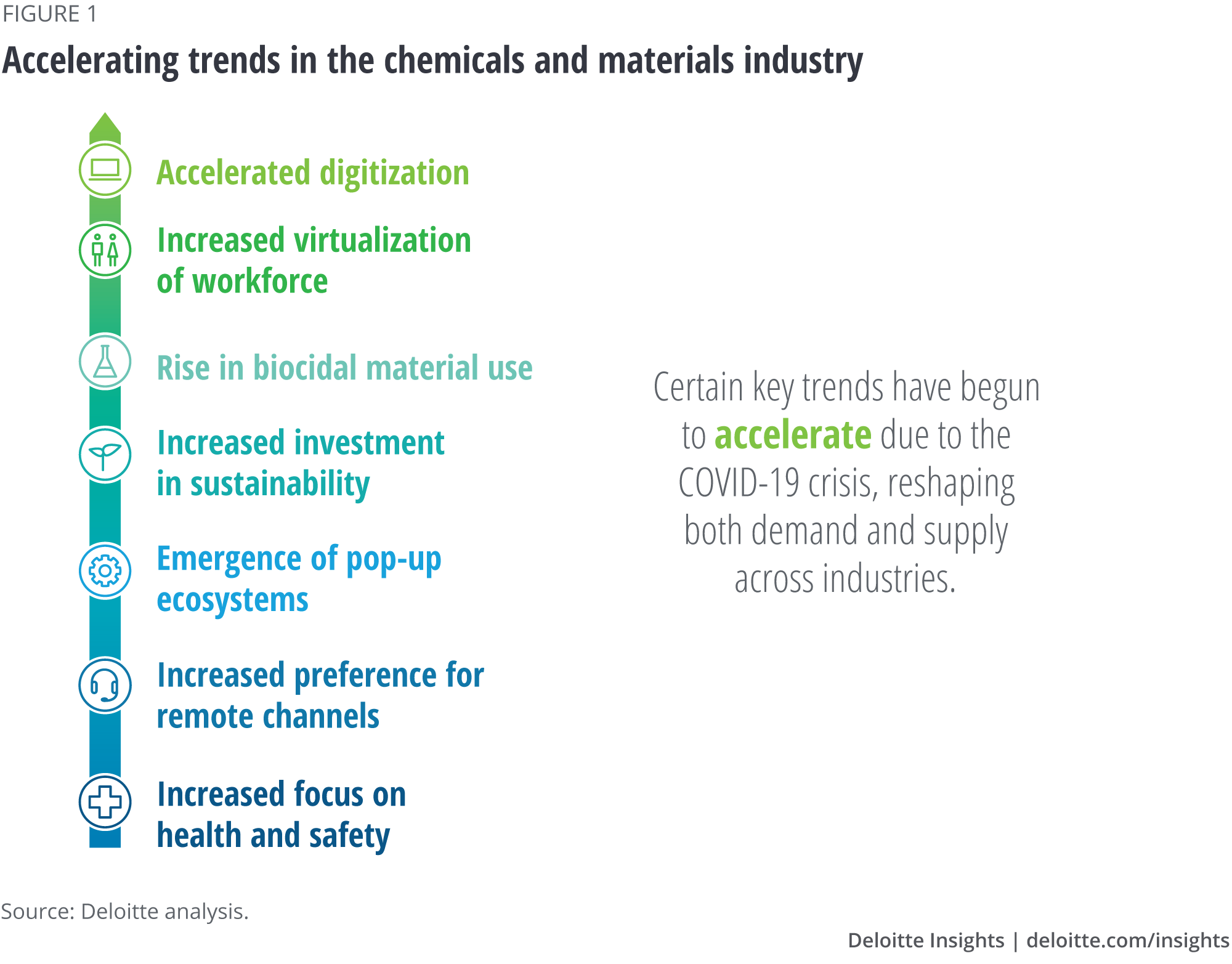

Accelerating trends

A clear strategy was articulated by a subset of interviewed chemicals CEOs, division presidents, and R&D leaders: Most financially strong companies intend to double-down on certain initiatives that they see as accelerating, and where investment now will enhance their competitive position in the future. This strategy will likely yield competitive advantages in the future because these initiatives are tied to underlying trends that are expected to accelerate (figure 1):

- Focus on health and safety: Consumers are demanding safety and precautionary measures from both brands and governments.

- Preference for remote or digital sales channels: More B2B and B2C interactions are taking place through remote or digital channels and experiences due to social distancing and restrictions.

- Emergence of pop-up ecosystems: Value chain disruption is likely to lead to more creative partnerships.

- Investments in sustainability and the circular economy: Environmental, social, and governance investments have seen a steady increase in inflows and better-than-average returns since the start of the pandemic.5

- Demand for biocidal and functional materials: The COVID-19 pandemic has created new growth opportunities for biocidal paints, coatings, and surfaces in public spaces such as hospitals and schools.

- Virtualization of the workforce: Organizations have already adjusted to working remotely and have begun to adopt new business models.

- Digitalization of core business processes: Adoption of contactless technologies and digital experiences (e.g., advanced analytics, 5G) has increased, driven by social distancing.

See the sidebars, “Digitalization of core business processes” and “Preference for remote or digital sales channels” for a more detailed examination of a few of these trends.

Digitalization of core business processes

While advanced digital technologies were already changing the business landscape, their applicability assumes even greater importance in today’s greater uncertainty. For example, digital technologies can help in rapidly reengineering products to reduce costs and improve the robustness of supply chains. Citrine Informatics, a startup using artificial intelligence (AI) for materials innovation, uncovered low-cost formulations in less than 90 days by evaluating, optimizing, and assimilating ingredient recipes and domain knowledge.6

Acceleration is expected in specific areas:

- The rise of open digital platforms that share product specifications across entire manufacturing ecosystems

- Capabilities that accumulate vast amounts of material knowledge from varied sources into a single, reliable, searchable format

- Machine-learning algorithms that help in developing new innovations, both in process improvement and product efficiency

Preference for remote or digital sales channels

It’s already a cliché that the COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the shift to digital. But many of the best companies seem to be going further, by enhancing and expanding their digital channels.

Until recently, the pace of business-to-business (B2B) commerce adoption in chemicals has been slower than other B2B industries. Chemical sales on US B2B e-commerce websites are growing at 3.7% compound annual growth rate (CAGR; over the period 2017–2020), compared with a CAGR of 13.6% for overall US B2B e-commerce sales over the same period.7 In a recent poll, two-thirds of 76 chemical industry executives shared that focus on other business priorities or limitation in capabilities as main reasons why the chemical industry, to date, hasn’t adopted digital commerce faster.

Reimagining the future of commerce in chemicals will likely require a shift to providing better customer experiences, including:

- A seamless e-commerce experience that enables customers to complete their entire transaction online, from initial research and purchase to service and returns

- Better access to all customers through various digital channels such as portals and marketplaces

- Deep analytics about purchases, customers, and markets, to create better customer experiences and thus more value

Many chemicals companies have already started on these activities to reimagine e-commerce.

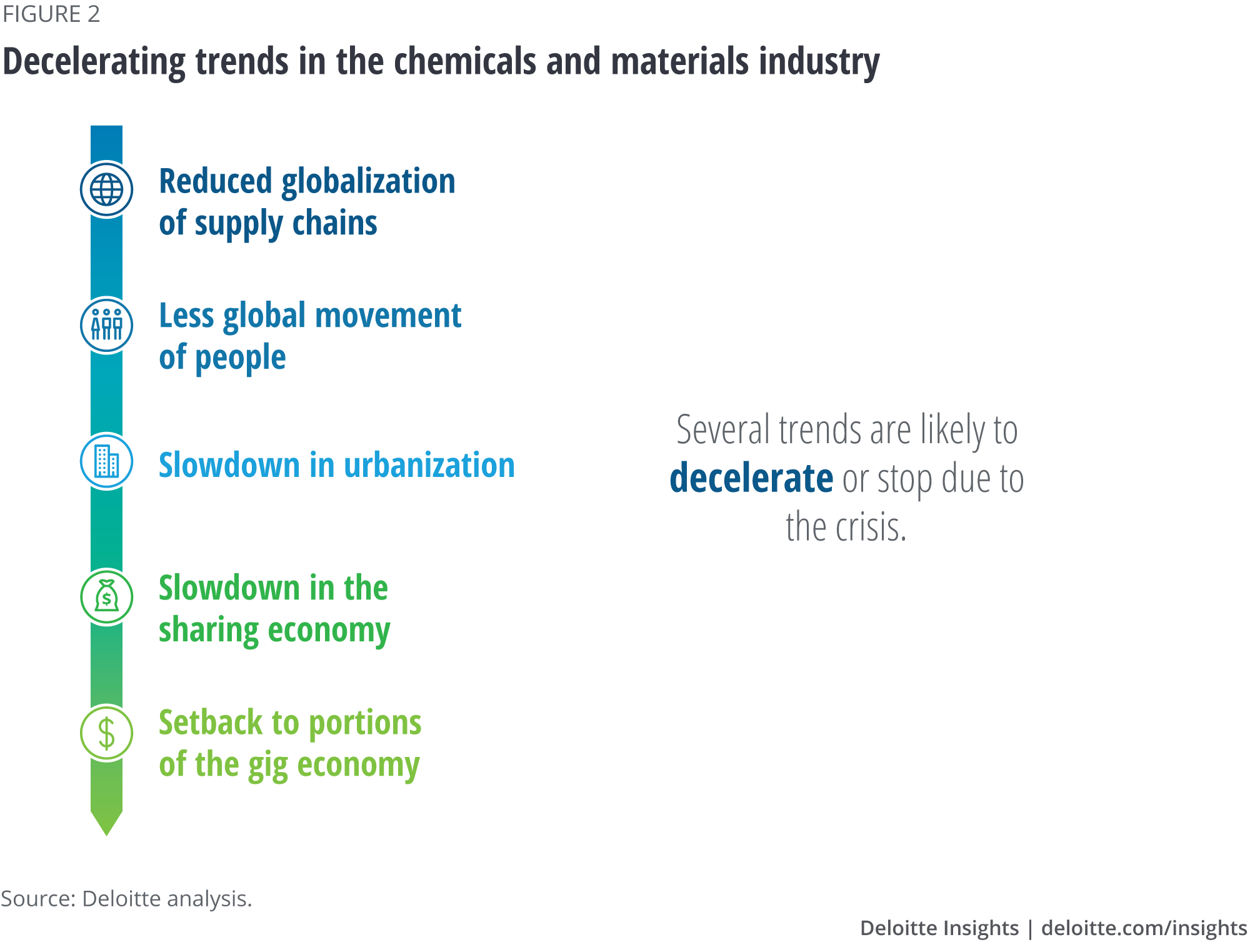

Decelerating trends

Apart from accelerating trends, we have also identified several trends across the industry that could decelerate as a result of the pandemic. This list is more uncertain and fluid, but from a post-2020 perspective, many of these trends indeed seem to be slowing. And while deceleration doesn’t mean reversal, it remains to be seen whether the deceleration will slow or stop over time.

The decelerating trends identified include (figure 2):

- Globalization of supply chains: More protectionist policies may push companies to “bring home” supply chains to mitigate regional risks.

- Global movement of people: Based on government travel restrictions, the movement of people across national borders may decrease.

- Sharing economy: Rising health concerns and virtual work may reduce demand for shared services and coworking spaces.

- Urbanization: Social distancing, amid rising fears of contagion, may reduce the likelihood of living and working in major cities.

- Portions of the gig economy: Demand for flexible or temporary labor has increased for higher-skilled engagements, such as coding and design, that can be delivered remotely, while social distancing has reduced demand for others, such as nondelivery transportation and cleaning.

Continuing trends

Comments from industry participants and our own research indicated that there are several trends central to the chemicals and materials space that are expected to continue apace (figure 3):

- Growth in production capacity for chemicals: Rising demand has forced global chemical manufacturers and integrated oil and gas players to constantly add new capacity. However, several capacity-focused capital expenditure projects have been deferred due to the pandemic.

- Accelerated energy transition: Electricity demand has fallen due to lockdown measures applied by governments, and yet total renewable generation has remained at precrisis levels with low electricity prices, which could accelerate the electricity system transition.

- Consumer preferences for sustainable products: Overall, the pandemic has heightened awareness of the close relationship between human health and the health of the planet, thus leading to a continued consumer-driven push for sustainable products. (See sidebar, “Consumer preferences for sustainable products” for more detail.)

- Societal concern for environmental issues: Chemicals executives have identified consumer support for reducing carbon emissions as one of the top drivers behind the industry’s transition toward a sustainable, low-carbon future.

Consumer preferences for sustainable products

The phasing out of some single-use plastics—bags, straws, and cups—in several countries and many US states provided a glimpse into the potential of such moves to disrupt the chemicals business. In this context, it was already clear that the adoption of sustainable practices was expected to gather pace. What is perhaps surprising is the unwavering support from industry executives for sustainability initiatives even during times of economic strain caused by the pandemic. And while it is clear that this view is largely driven by the commitment to sustainability and climate change issues, there is also a possible US$120 billion market opportunity (in the United States and Canada) for plastics and petrochemicals from recovering waste plastics.8

Chemical companies will likely be at the forefront of such sustainable practices by developing processes such as closed-loop recycling, in which polymers can be chemically reduced to their original monomer forms so that they can be processed or repolymerized and remade into new plastic materials. In addition, alternatives at chemical companies’ disposal include materials that are more easily recyclable or bio-based. However, for this trend to be sustainable, consumer behavior must also shift toward embracing and using such materials, often at a higher price point.9

Our analysis of the industry executive interviews generated deeper insights into the specific impact of the trends on the chemical and materials sector.

For example, a focus on workplace safety has been a hallmark of the chemical and materials sector since the establishment of Responsible Care (first adopted in Canada in 1985, and then in 1988 in the United States). The American Chemical Council has reported that voluntary actions by chemical companies routinely go beyond what is required by regulations.10 This focus on employee safety seems to have facilitated a shift to increased focus on hygiene and health in both offices and production units. Indeed, this was a topic emphasized by 100% of the executive interviewees. Of course, personal protection disposables and equipment itself is made from specialty materials such as spun-bound polyolefins, transparent engineer thermoplastics, and hand sanitizer formulations. Beyond increased demand for these well-established materials, there could be an increased demand for functional materials, particularly biologically active materials—including biocidal paints, wearable sensor materials, and, eventually, truly “smart surfaces” made from chromatic polymers that can indicate they are pathogen-free.

The emergence of pop-up ecosystems, although initially an emergency response to a short-term crisis, will likely accelerate. Many executives interviewed quite proudly described how their organizations were able to leverage their capabilities and assets to address shortages and needs. The arguably best-known such ecosystem is automotive original equipment manufacturers’ partnering with medical device companies to manufacture rescue ventilators in idle auto factories. Another pop-up is a chemical and paint formulation capability being repurposed for hand sanitizer production. Signs indicate that this shift may be more permanent, as chemical and materials companies seize the opportunity to move further downstream into higher-margin application.11

Of all the accelerating trends, perhaps the most counterintuitive has been the increased focus on sustainability. While COVID-19 has clearly reminded consumers about the value proposition for plastics being used to protect people, food, and health care products, the commitment to initiatives such as green and blue hydrogen (green—produced via renewable energy electrolysis; blue—with carbon capture) and chemical recycling seems to remain as robust as ever. One study noted that recently there have been more than US$300 million invested in startups on plastics recycling in 2019 alone.12 This is apart from the many internal ventures that are underway in companies’ R&D departments focused on sustainable products and solutions.

Decelerating trends can lead to equally profound shifts in product supply and end-application demand. For example, there was consensus amongst interviewees that globalization has reached its peak and is likely, at least for now, in retreat. It is obvious to all that there is far less movement of people.

Regarding mobility, the International Air Transport Association has recently forecasted that 25% fewer planes will be needed over the next five years—with the obvious impact on the materials and chemical tiers that serve that sector.13 Changes in urbanization trends impact consumption of building materials, ranging from interior finishes to high-tech insulation. The future of super-expensive urban office buildings thus seems suspect. Housing data is hinting at the start of a “flight to the suburbs”; even as lockdowns have been eased, and many still prefer to work from home out of caution or convenience. Of course, a suburb and exurb boom would drive the consumption of building materials needed for that construction.

There is no question that the sharing economy, be it cars or high-rise offices, is on hold for the foreseeable future. Ride-share startups have pivoted from massive hiring to double-digit percentage layoffs of their workforce.14 There seems to be much less optimism, overall, about the inevitable march to a complete gig economy. A permanent move away from shared mobility would correspond to an increase in personal car ownership. China has reported increased sales to first-time car owners as many consumers perceive car ownership to be safer and to impart more autonomy than full dependence on mass transit.15

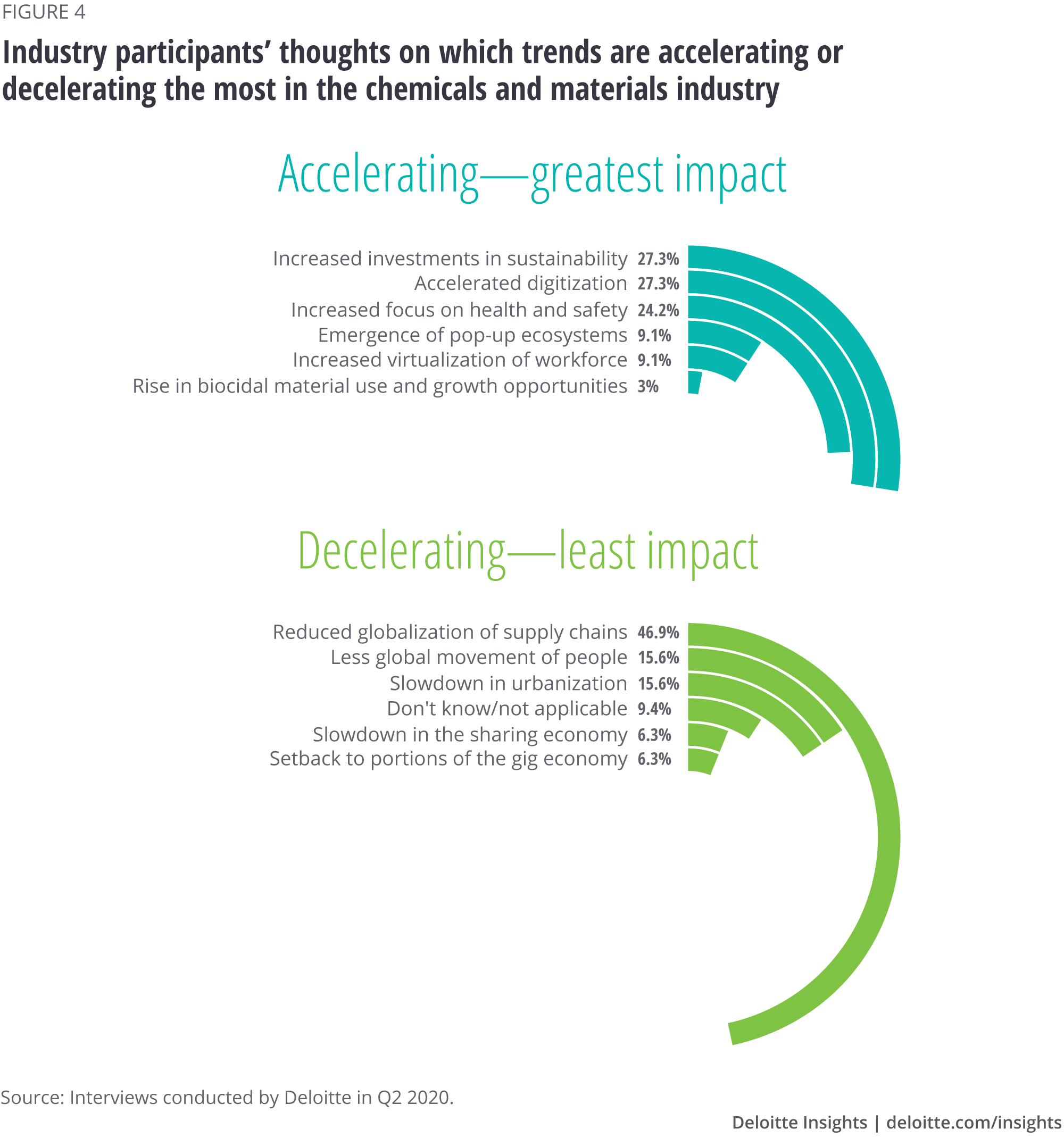

To further validate the accelerating and decelerating trends, an audience of 53 chemicals and materials managers and executives were asked to vote on the relative impact of the trends on the chemicals and materials sector (figure 4). The results broadly confirm the conclusions of the primary and secondary research. Of particular note were the large percentage of votes for sustainability and increased digitization, which together accounted for more than half the votes for accelerating trends. The top deceleration trend was globalization, as judged by almost 50% of chemical executives.

Future scenarios and their implications

The discussions with executives and the secondary research were leveraged to build out scenarios that considered the longer-term impact of the pandemic and the emergence of a new status quo. But what exactly are scenarios, and why are they essential for planning?

As Yogi Berra may (or may not) have said, “It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”16 The events related to the emergence and spread of COVID-19 have underlined this point, as communities and companies had to reverse plans that were well crafted but not agile enough to accommodate dramatically changing conditions. Scenario planning accepts that it is impossible to predict the future precisely. What is possible is to focus on key uncertainties, and then build out scenarios that can be used for business planning around these uncertainties. One trades unrealistic precision for robustness and resilience, which is a good trade in business.

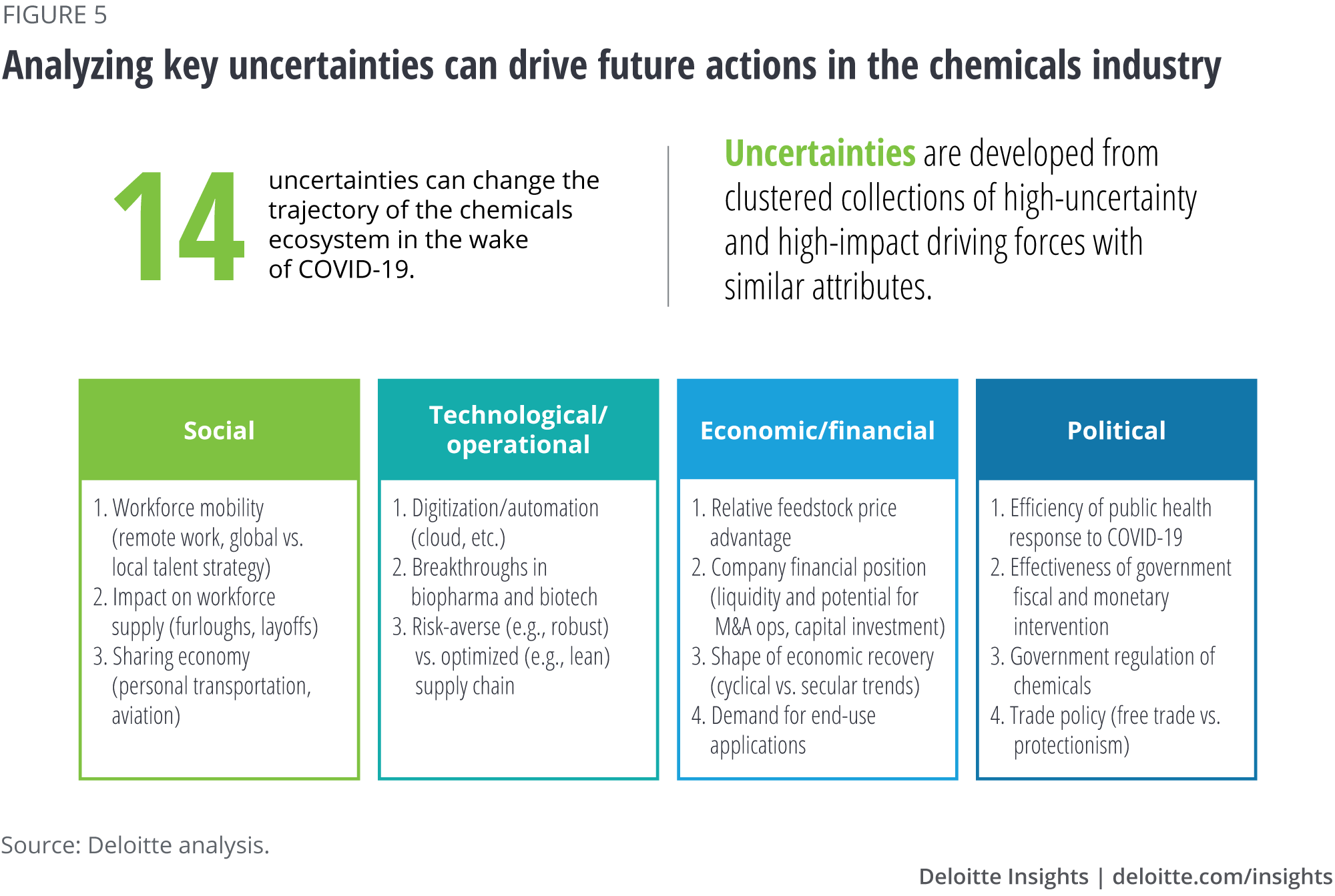

The first task is typically to identify key uncertainties. From the research, a total of 14 key uncertainties emerged (figure 5). Broadly, these were categorized as social, technological/operational, economic/financial, and political. Although scenario techniques require narrowing down to two specific uncertainties, it is useful to consider all uncertainties. Perhaps not surprisingly, eight of the 14 identified in our research were either economic or political uncertainties. Others were more closely aligned with social and technological uncertainties, and some, such as breakthroughs in biotechnology, were quite unique to a public health crisis.

Through an iterative process engaging leaders and subject matter specialists from Deloitte’s chemicals practice, the 14 were distilled into two paramount uncertainties:

- How severe and widespread will the pandemic be?

- Will it trigger permanent changes in workplace and consumer behavior?

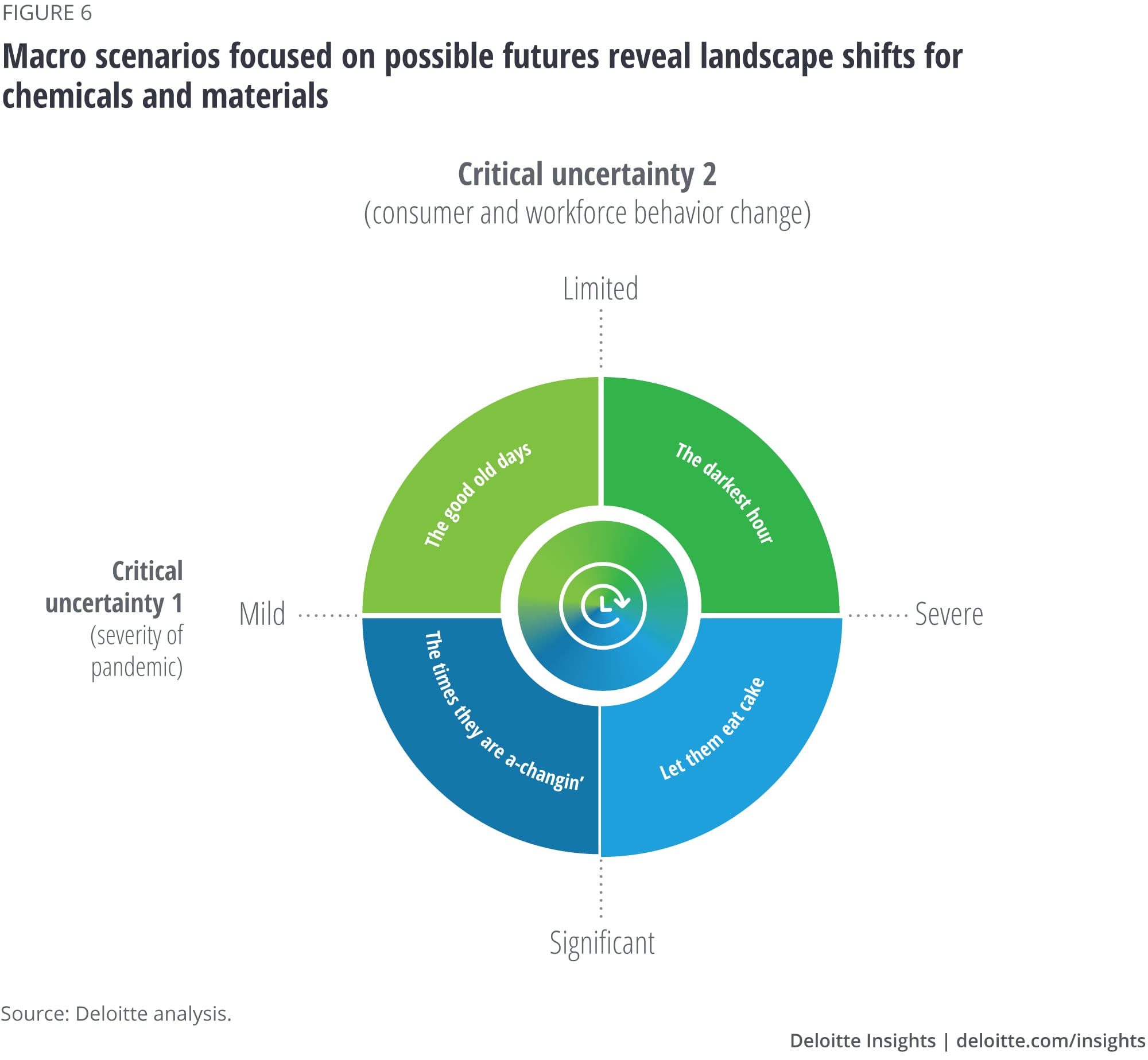

Crossing these two uncertainties generates an X and Y axis (figure 6). The X-axis considers the severity of the pandemic itself: Is it like SARS, which disappeared, or like the 1918 flu, which spread across the globe in multiple waves? The Y-axis considers human behavior: Is there a coordinated and universal response from consumers and workers that indicates a fundamental behavior change, or is there a disparate and or muted response?

Considering both the X and the Y axes generates four scenarios (figure 6), while one doesn’t know which one will turn out to be true, each of these scenarios is distinct, and companies will want to understand potential implications of each on their specific businesses.

Considering each scenario in turn:

In “The darkest hour,” the pandemic rages on, and aggregate cases follow an exponential curve of increasing infections. Although intense R&D efforts make progress in vaccines and therapeutics, they have not advanced enough to suppress the pandemic. There is an uncoordinated response across countries and regions. Behaviors of people and companies are equally mixed, with behavioral changes occurring, but disparate and constantly changing. The net impact is a series of rolling shutdowns of varying degrees, and an overall suppressed economic recovery and resulting business impact.

Similarly, in the “Let them eat cake” scenario, intense R&D efforts make progress in vaccines and therapeutics, but they have not advanced enough to suppress the pandemic. At the same time, people and businesses do make coordinated and substantial changes to their behavior, and this leads to significant shifts in demand and catalyzes business model shifts. Depending on the sector, this leads to depressed demand (for example, aerospace materials) and big opportunities (surfactants and medical polymers).

From the vantage point of the second half of 2020, “The good old days” scenario seems very unlikely but still needs to be considered. Through intense R&D efforts and clinical breakthroughs, the pandemic begins to be suppressed. Behavioral changes are temporary as people and business resume old habits. This scenario would manifest itself in a snap-back economic recovery with full planes, traditional schooling, and live sports.

“The times they are a-changin” is perhaps the most interesting for chemicals and materials. As in the third scenario, advances in research and clinical settings begin to suppress the virus. There are, however, big and permanent changes in consumer and worker behavior. This creates losers but also winners with significant shifts in demand flows. For example, an air transport technology that scrubs the cabin air and is outfitted with all antimicrobial surfaces would thrive in this scenario.

As one might expect, the impact on the chemicals and materials sector in each scenario is as varied as the sector itself. Indeed, the specific “products” of the industries’ manufacturing processes are liquids and solids, but that is not how society and the economy experience the discoveries of chemicals and materials innovations—instead, the outputs of the industry are experienced via the specific application space. For example, the bill of materials for health care personal protective equipment (PPE), medical devices, and disinfectants are all purely the products of the chemical industry, often as part of a complex formulation.

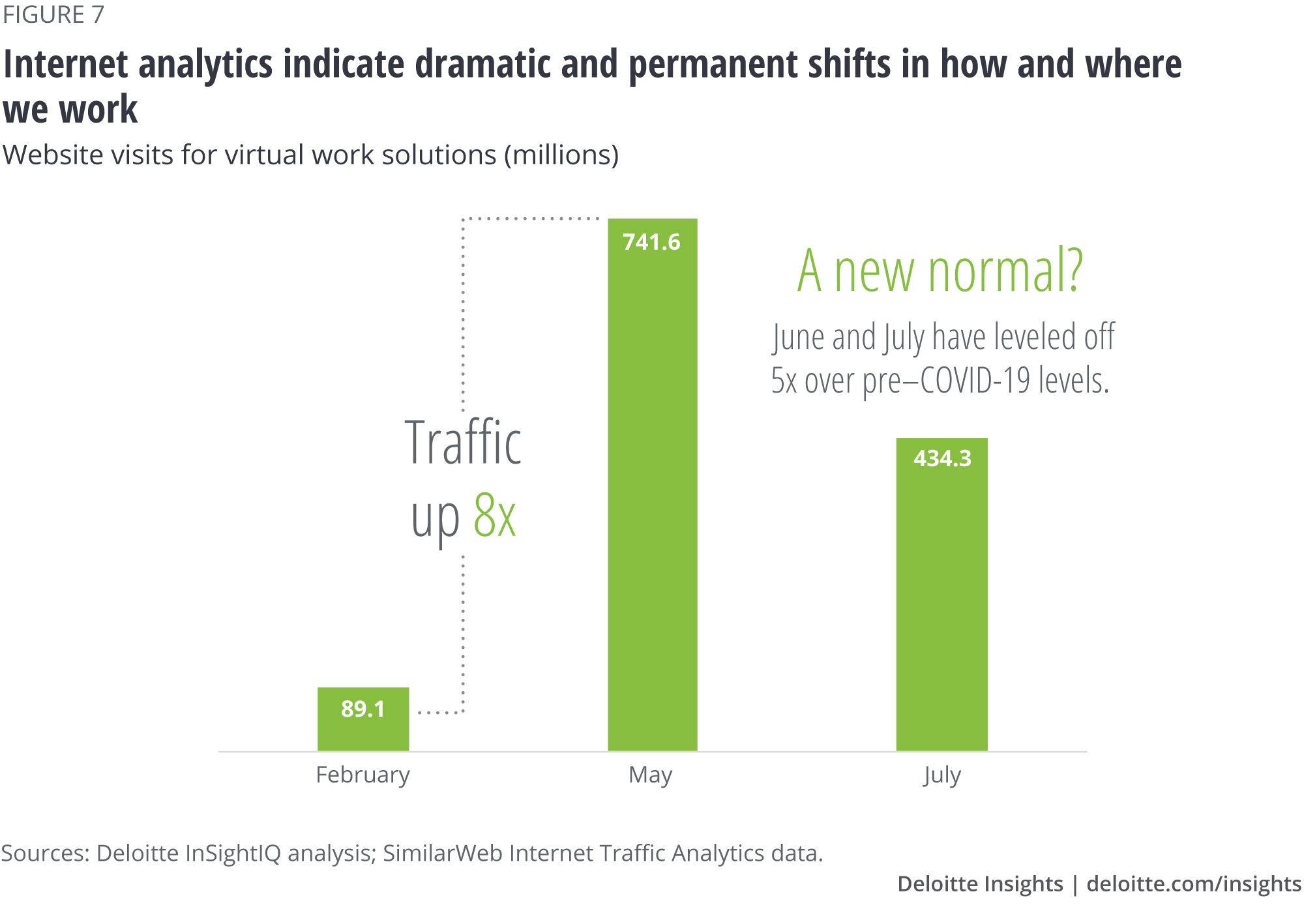

It seems obvious that the length and depth of the public health crisis will directly impact the economic conditions. While true, the longer-term impacts will likely also be driven by the changes in consumer and worker behavior—the Y-axis in the scenarios. Some early views from the second half of 2020 already point toward enduring shifts. This can be seen in real-time data such as visits to websites seeking “virtual work solutions” (figure 7).

Given these changing trends, chemical companies should focus on these new growth opportunities and extract more from their existing assets and resources. This highlights the importance of an “application-focused” view of the industry, where the key could be to follow the “pull” on produced materials from end applications.

A road map for the future

In order to focus on new growth opportunities and extract more value from current resources and assets, executives should keep an eye on the larger trends shaping consumer preferences and the broader market environment. The goal should be not to predict the future, but rather to track the two key factors—the pandemic’s impact on the economy, and changes in consumer preferences and behavior—in this rapidly evolving situation.

While the trajectory of the pandemic can be tracked through numbers such as new infection rates and testing results, one key element to watch will be the policies implemented to curb the spread and the extent to which these measures depress or delay economic reopening in various regions. As communities have reopened, traffic has quickly increased, lifting gasoline demand. In addition, purchasing activity has partially resumed, bringing some relief to the consumer sector, and new unemployment claims have fallen as people begin to return to work. These were welcome developments, but further progress is still linked to the containment of the virus.

Similarly, executives should track not only the underlying changes in consumer behavior already underway before the pandemic, but also more recent changes in response to the pandemic, such as increased demand for PPE and health- and safety-oriented products. In addition, consumer preferences will continue to evolve regarding contactless interactions and new ways to receive services. Companies that can be the first movers in this new landscape and take an “application-focused” view will likely reap longer-term benefits.

Companies could be well served in the current market by continuing to develop three key competencies:

- The pandemic has revealed the fragility of global supply chains, leading many companies to explore new more “local” supply chains. The chemicals industry responded with great agility to these challenges and will likely be called on to do so again in future disruptions. The companies that are able to quickly retool production lines and adjust smoothly to pop-up ecosystems might enjoy a competitive edge.

- The second competency is the “variabilization” of costs (agility in response to need). For example, the ability to quickly expand production and workforce in response to a volatile situation will likely continue to be tested. Similarly, the need to streamline operations and increase operational agility will likely continue to be important.

- Finally, continued progress on digitalization of operations and market sensing could increase companies’ competitiveness. The ability to use advanced market sensing, apply AI and other technologies to decision-making, and reduce silos within a company through common access to advanced analytics could reduce response time to critical market changes.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More in Oil, gas & chemicals collection

-

Energy Transition Article

-

Innovation in chemicals Article4 years ago

-

Decoding the O&G downturn Collection

-

Moving the US shale revolution forward Collection

-

Down but not out Article5 years ago

-

One Downstream Article5 years ago